In case anybody actually reads this blog, I have migrated it to Substack here:

European Macro Perspectives

Blogs about current (mostly European) macroeconomic developments through the prism of someone in between academia and journalism.

Monday, May 8, 2023

Sunday, May 7, 2023

Short argument for optimistic scenario for core euro zone inflation

The optimistic case rests one two arguments. First, some

segments of core inflation should benefit from reversal of the shocks that

drove prices higher last year. For non-energy industrial goods this is about

lower energy prices feeding through to lower industrial good prices, and about

unwinding supply bottlenecks leading to lower equilibrium prices. For services

this is about price increases related to re-opening going into reverse.

While all of this is possible – I would even venture to say

that the question is of magnitudes, not whether it will happen - on its own it

is unlikely to inspire that much optimism. Especially, when the counterargument

is that wages are increasing pretty rapidly by historical standards. And here

in comes the second argument: While nominal wages are increasing

at fast pace and will continue to do so, what matters for inflation outlook is

the level of real wages. And the key point is that even with

rapid increase in nominal wages, real wages will only come back to pre-pandemic

level in 2025, as per ECB:

And in this lies the optimistic case for euro zone core

inflation. It is really the counterargument for pessimist case, which is built

around wages. In other words, at the heart of the optimistic case is that the

argument based on wages carries much less weight than people think. Sure,

ceteris paribus wages increasing rapidly implies higher inflation, but that

on its own does not imply high inflation. The reason is that so far

prices have increased without corresponding increase in wages, so that now wages

have scope to increase without a need for prices to increase. So the optimistic

case for core euro zone inflation is built around the simple argument that previous

price increases that outpaced wage increases created a cushion in which effect

of wage increase can be absorbed.

The other way to think about this is in terms of profits:

after profits rose significantly over last 3 years, there is a large scope for

firms to absorb higher wages without the need to increase prices. Again,

chart on profits from the ECB:

Add to this that the lower input prices (energy and food)

provide additional scope to absorb higher nominal wages even without lower

profit margins - decrease in one input cost would offset increase in

another input cost – and you end up with plausible optimistic case for

euro zone inflation.

Ultimately, given that we will be gradually returning to

pre-pandemic world in terms of external costs (energy, food, commodities and

transportation), in terms of supply in our economy (cars, airlines) and in

terms of demand (holidays), return of real wages to pre-pandemic world should

not mean high inflation. It is just return to an old equilibrium.

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

Does it matter whether euro zone inflation is supply caused?

A brief email exchange with Adam Shapiro made me realize one

thing: Whether inflation is supply caused or not makes potentially a lot of

difference. Why? Because it could/should influence our thinking about the

future inflation outlook insofar as decrease supply might reverse itself eventually.

To see this consider the case of airline ticket prices in

euro zone I

discussed before. Accepting that the high prices in this segment are demand

driven but supply caused, and assuming that airlines will eventually re-learn

how to operate as efficiently as before the pandemic, then you would expect

prices to decrease significantly without a decline in demand. In other

words, this segment would feature deflation in absence of anything else. Including

action by the central bank, a quintessential transitory inflation. Hence, the

resulting outlook for inflation would be quite optimistic.

On the other hand, if the high prices are solely about demand

being too high relative to what was normal during the pandemic, then only decrease

in demand will help as supply simply cannot increase that far (at least not in

reasonable horizon). In this case prices/inflation will remain high as long as

demand is not brought back to its position. Hence, the resulting outlook for

inflation is very different: Assuming that there isn’t a recession, inflation

will prove sticky, and only through monetary policy demand management will we

force it back to target.

Therefore the distinction between driven/caused is important.

If it is demand caused, we inflation will be sticky. If it is supply caused

then we have hope for inflation to moderate, even if it currently is

demand driven inflation.

Monday, April 10, 2023

Simple smell check whether eurozone inflation is caused by demand

Putting all the arguments aside, do the results for euro zone inflation decomposition pass simple “smell check”?

Consider using comparison between US and euro zone as one

such simple smell check. The idea is straightforward. I think following

comparative statements are not contentious:

- US aggregate demand is much “hotter” then euro zone – especially on the goods side, but also more broadly. To see that we only need to compare the change in GDP relative to pre-pandemic level, and especially the change in goods consumption.

- US had significantly more fiscal (and maybe monetary) stimulus than euro zone. Simple comparison of total fiscal expenditures during the pandemic period suffices to make this point.

- US had significantly smaller energy and food shocks, implying smaller indirect effects on rest of CPI. Again, comparison of the market prices for electricity, natural gas, food commodities make this clear.

All of these should mean that the US inflation should be

significantly more about demand than supply compared to euro zone

inflation. Is this what we conclude using the methodologies discussed in previous

post? Surprisingly, no. For both US and euro zone, roughly half of core

inflation is accounted for by demand-driven inflation:

Problems with identification of demand and supply driven inflations

The big macroeconomic question of drivers of current

inflation also found its way into formal empirical analyses. The starting shot

of this discussion (probably) dates to Adam’s

Shapiro paper using VAR methodology, which was later replicated

for euro zone by ECB authors. Similarly, Ricardo Trezzi and co-authors have new

paper using similar VAR methodology.[1]

Mostly, these papers lead to conclusion that both supply and

demand are driving inflation, and roughly to a similar degree. For example,

here is picture for euro zone from the ECB authors (all other pictures also are for euro zone):

However, looking at considering the picture from previous

posts,

what these papers are really saying is that the most recent shock has been a

demand shock, as we observe both increase in prices and quantities. This is the

example of airline tickets, as in 2022 we observed increase in prices and

quantities. So, using the terminology of “driving” vs. “causing”, these estimates

are estimates of what is driving the inflation, rather that what is causing

it.

However, even accepting this, there are reasons why these

estimates might be imperfect. This has to do with several problems with their

identification strategy, which while being neat and probably the best we can

do, is still far from perfect for the messy reality. Therefore, I personally

think of these estimates as good starting point, but one that probably provides

an upper bound on demand-driven component of inflation. Below is discussion of

several reasons why.

Identification of forecast errors

All the papers proceed along similar way. They first

estimate VAR model, which links price and quantity developments to previous

price and quantity developments in the typical autoregressive fashion. For each

period they then decompose the actual movement in the prices and quantities

into movements that are “expected”, that is predicted by the model in absence

of the shocks, and movements that are caused by shocks, i.e. not predicted by

the model. The difference between those are the forecast errors, and these

forecast errors then form the basis of the identification strategy: a

combination of positive forecast errors for quantity and prices suggests demand

shocks, while negative forecast error for quantity and positive for price

suggests supply shocks.

However, this identification strategy crucially depends on

identification of forecast errors. And the identification of what is “forecast

error” of course depends on what is “expected”. And therein lies the problem.

While autoregressive process is a reasonable description of evolution of

macroeconomic variables before the pandemic, it is pretty woeful description of

developments during pandemic. Why? Because during pandemic shocks are reversed

rather than propagated.

For example, if you end up with another wave of pandemic in

fall of 2021, this means a decrease in quantity of flights, which is however

expected to be reversed pretty soon. In other words, a negative movement is

followed by positive movement. In contrast, VAR model will expect that that negative

movement will be followed by further negative movements. While this is entirely

plausible description of usual developments, we are not in the realm of usual.

In other words, the model is estimated on data coming from different

data-generating process than the recent observations.

A nice example of this comes the paper by Ricardo Trezzi an

co-authors. Consider the period from July 2020 onwards. According to their model

there was a large positive forecast error for output (proxied by industrial production),

meaning that output was higher than the VAR model predicted.

But is this reasonable? In other words, was it reasonable to

expect output to remain at July 202 levels throughout the 12 months after July

2020? I don’t think so – there was general expectations for economic output to

increase following the drop and initial rebound during pandemic. In other

words, from non-model perspective, there wasn’t a surprise increase in

output, and hence there wasn’t a positive forecast error for output. Of course,

if we were to change the forecast errors for the model variables, then we would

also end up with completely different set of structural shocks, which we are

after.

The point is that the VAR models are going to systematically

consider post-pandemic rebound as positive forecast errors in terms of

quantity. And since this rebound naturally coincides with increases in prices, then we will conclude

that these are positive demand shocks, and hence label resulting increase in

prices as “demand driven”. Of course, insofar as these increases in quantity

are not real surprise – most forecasters expected these increases in output as

part as post-pandemic rebound, so they are only surprise in the context of our

VAR model – we are misidentifying forecast errors and hence misidentifying the

shocks.

The ECB authors actually point towards this problem in the

conclusion to their piece, highlighting the same issues I discussed in detail

here:

In addition, developments

in quantities and prices have clearly been exceptional since the start of

the pandemic and have been influenced by many special factors, making it more difficult

to build a reliable model as a basis for classification based on the

signs of its errors.

This is exactly the crux of the matter: to identify

structural shocks based on sign restrictions, you need to identify forecast

errors for your variables. And for that you need a model which will do this

reliably during the pandemic period, which is bit too much to expect from model

estimated on pre-pandemic data. In other words, I would not be raising this

issue if we were talking about overall pre-pandemic period, where I do buy that

VAR model can identify shocks; pandemic period is different metter.

Identification via sign restrictions and issue of timing

Related problem of the identification strategy is the

problem of timing of shocks and effects and their relationship to sign

restrictions. The idea behind the identification strategy is that when demand

or supply shock happens, it affects prices immediately. This corresponds to the

micro-economic concept of equilibrium. And while this is reasonable assumption

for some markets, it is not for other markets, simple because there are

sometimes delays in reaction in prices. This can be because prices are set by

firms, and such price settings is updated only once in a while. Or it can be

simply because price discovery takes time.

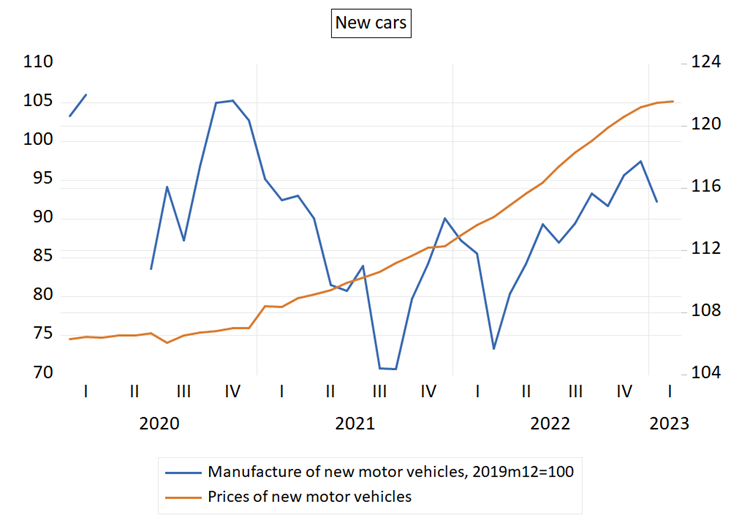

For the former, consider new car prices in euro zone. We

know that car production has collapsed in 2021 due to chip shortage (see picture

below). This is unambiguously a negative supply shock, which in standard

microeconomics should mean higher prices in 2021. However, looking at

the time series plot of new car prices you would conclude there was major shock

in 2022, not in 2021. (Of course, there

was additional shock coinciding with the invasion, but that was quickly

reversed).

Why is this a problem? It is problem because of the

concurrent evolution of output. New car production has rebounded throughout

2022, as the supply chain problems gradually unwound. From perspective of our

VAR model this is going to be unexpected increase in quantity. And this

unexpected increase in quantity coincides with unexpected increase in price.

Therefore, our model will assign this increase in price to a demand shock,

consistent with the identification strategy based on sign restrictions. But we

know that the increase in prices is not due to demand shock, or at least not to

any significant degree. Instead, it is a delayed price effect of previous

supply shock. This is then example how the identification strategy fails in

presence of delayed price effects due to price adjustment being a gradual

process in situation when firms set prices.

Meanwhile, used car prices are best described as determined

by price discovery, rather that set by firms, and hence provide example of slow

price discovery. Used car prices in euro zone follow similar profile as new car

prices, only more extreme: there is no price increase in first half of 2021, and

significant increase comes only from 2022 onwards.[2]

Again, this is a result of supply chain problems affecting car production

throughout 2021, which showed up in price data only in 2022. But insofar as

2022 is time when quantity of used cars traded increases, corresponding to

increases in new car production, we will again observe higher quantity and

prices together, and assign this to demand shock.

These are just two examples of these kind of issues, illustrating

a broader point: our identification strategy based on sign restrictions is

going to fail if the changes in prices are delayed relative to the shocks

affecting output.

Multiple shocks

Another related issue is the issue originating in multiple

shocks. In principle, the example discussed in my previous

post was a somewhat philosophical example of possible problems caused by

multiple shocks. But this problem can arise even in more prosaic situations.

The source of the problem is that the identification

strategy relies on the overall change in quantities, but this can be misleading

if supply and demand shocks happen together and push in opposite direction.

Most naturally, in the post-pandemic, post-invasion period we are likely to get

negative supply shocks and positive demand shock. This is problem for two

reasons.

First, we will end up assigning the whole price effect to

either demand or supply shock, even though it is due to both. Second, the

overall quantity effect does not need to indicate which shock was “bigger”, as

the quantity effect also depends on the relative elasticities. Picture below

shows a large negative supply shock and small demand shock which nevertheless

result into higher quantity.

Most importantly, these two problems interact together. In

the above example looking at prices and quantities we assign things to demand

shock, as quantity and price increased. And we will assign the whole price

change to demand shock.

As an example, consider restaurant prices. In the aftermath

of the Russian invasion of Ukraine the supply has decreased dramatically in

that restaurants were willing to supply only at much higher prices as their

costs have surged. At the same time, demand has likely increased due to the

post-pandemic re-opening. If we are willing to assume that demand at this point

in time was inelastic – people were eager to go to restaurants after 2 year

hiatus, then we could easily assign the complete increase in prices to demand

shock, even though most of it was due to supply shock.

This is made worse by the delayed price effects. Presumably,

pandemic itself meant negative supply shock in so far as many restaurants did

not survive the lockdowns. But this was likely not reflected in prices during

the pandemic, when restaurants fighting for survival were unlikely to increase

prices. This price increase came only when the re-opening happened. And at that

point we observe increase in quantities and prices and conclude we are seeing

positive demand shock. In reality, increase in prices was at least partly, if

not dominantly down to earlier negative supply shock.

The general point is that in presence of multiple shocks

going in opposite directions, sign restrictions might lead to misleading identification.

Again, to their credit, the ECB authors point out this problem in their

conclusion:

Second, the disaggregated approach cannot quantify how large the supply and demand contributions are for each component. This could introduce a bias if, for example, the role of supply factors for components classified as predominantly demand-driven is on average much larger than the role of demand factors for components classified as predominantly supply-driven.

In other words, in presence of multiple shocks, the identification based on sign restrictions becomes potentially problematic.

Conclusion

Overall, while the identification approach based on sign

restrictions in VAR models are clever and definitively a step in the right

direction - especially those based on detailed data - I think that people should

not be putting so much weight on the resulting estimates. I would be willing to

put a lot of weight on them during normal periods where we are not dealing with

multiple major and unprecedent shocks. However, in current environment where there

are likely multiple shocks, that are both large and unprecedented, I think that

the estimates need to be taken with large grain of salt. And this is not only because

potential noisiness of the estimates, but also because I think that with large probability

the estimates are also biased: note that the problems will typically lead to

higher estimate for demand component, rather than higher estimate of supply

component.

And then there is also the related issue of interpreting

these results, something that I touched upon in previous

post. Even if we accept the estimates of demand driven component at face value,

these estimates do not say what some people claim they do. Specifically, they don’t

say that aggregate demand is running abnormally hot; at most, they might imply

that aggregate demand is has (a) recovered strongly after the pandemic shock,

(b) has recovered to larger degree than aggregate supply.

[1] While

there are other papers using different approaches, I will focus only on the

papers using VAR methodology here.

[2] At

least as far as CPI data can be trusted – anecdotal evidence would suggest that

prices started rising significantly already in 2021, same as in US. But of

course, given its nature, it is hard to know how much should we trust anecdotal

evidence.

Thursday, April 6, 2023

Example for demand driven but supply caused inflation

As an example for the demand-driven but supply-caused

perspective, take airline tickets. When pandemic hit there was a total

annihilation of demand and supply, as nobody was allowed to fly. Afterwards,

supply partially recovered as operation of airlines was allowed, but demand was

suppressed, as nobody really wanted to fly given the associated conditions. This

state persisted until re-opening was in full swing. This brought rebound in demand

and with it also dramatic increase in prices. This can be seen in following figures:

left panel shows the development in quantity, while right shows the prices.

Is this increase in prices demand-driven or supply-driven?

Clearly, this corresponds to a demand-driven increase in prices, given that in

2022 increase in prices coincided with increase in quantities. But does it make

sense to assign increase in airline ticket prices to increase in demand? Sure,

it did come as a result of the rebound in demand. But at the same time, the

quantities remain well below their pre-pandemic levels, so they are not above

normal, which means that it cannot be straightforwardly concluded that extreme

prices are result of extreme demand.[1]

Rather, the story is probably as follows: re-opening led to

normalization of demand, maybe slightly above normal demand. This was

met with supply that was significantly lower than pre-pandemic normal, which

can be seen in how the quantities flat-lined once their reached 85%. As a

result, prices reached well above normal levels. While labeling inflation as

supply or demand driven is straightforward, labelling it as supply or

demand caused is somewhat harder. That said if one category has to be

chosen then I would certainly opt for supply. Why? Because it is the supply

which is further away from pre-pandemic normal.

The main point, then, is that with more refined terminology

we can have both demand-driven and supply-caused inflation labels. We can say

that the recent rise in flight ticket prices is driven by rebound in demand,

but that the abnormally high flight ticket prices are caused by shortfall in

supply.

I think this story of airline ticket prices applies more

generally. What we have been observing since beginning of 2021 onwards has been

normalizing demand hitting below normal supply, which led to above normal

prices. Together with airline tickets it applies to many travel-related

categories, albeit with some of them I would argue it is more about

(temporarily) above-normal demand. It also applies to cars, where it is harder

to argue that demand is higher than before pandemic. And in some sense it also

applied to euro zone energy, where demand was abnormally low during pandemic,

and then in rebounded to meat depleted supply; of course, later on a decrease

in supply became dominant driver.

[1] Of

course, lower than pre-pandemic quantities does not on its own imply that

demand was lower than normal, because we also have to contend with the supply

side of the story. Simply, output can be lower even with demand above pre-pandemic,

if decrease in supply was large enough.