As an example for the demand-driven but supply-caused

perspective, take airline tickets. When pandemic hit there was a total

annihilation of demand and supply, as nobody was allowed to fly. Afterwards,

supply partially recovered as operation of airlines was allowed, but demand was

suppressed, as nobody really wanted to fly given the associated conditions. This

state persisted until re-opening was in full swing. This brought rebound in demand

and with it also dramatic increase in prices. This can be seen in following figures:

left panel shows the development in quantity, while right shows the prices.

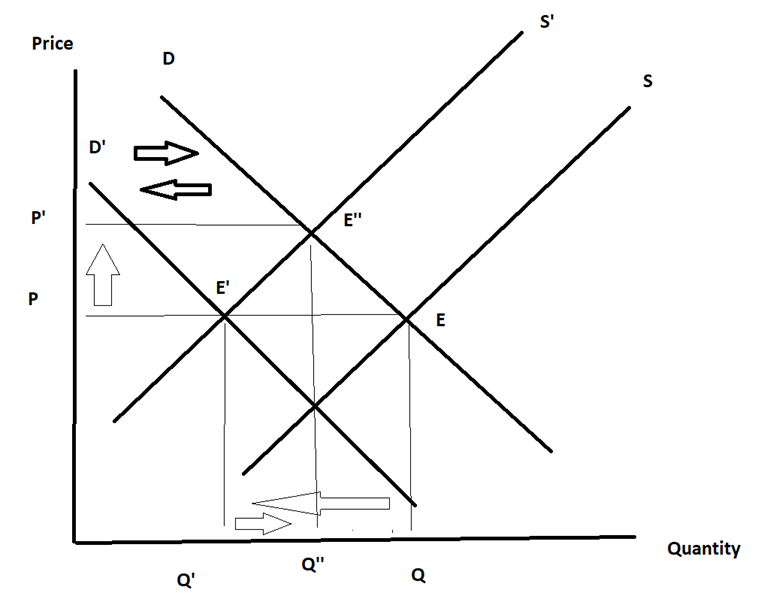

Is this increase in prices demand-driven or supply-driven?

Clearly, this corresponds to a demand-driven increase in prices, given that in

2022 increase in prices coincided with increase in quantities. But does it make

sense to assign increase in airline ticket prices to increase in demand? Sure,

it did come as a result of the rebound in demand. But at the same time, the

quantities remain well below their pre-pandemic levels, so they are not above

normal, which means that it cannot be straightforwardly concluded that extreme

prices are result of extreme demand.[1]

Rather, the story is probably as follows: re-opening led to

normalization of demand, maybe slightly above normal demand. This was

met with supply that was significantly lower than pre-pandemic normal, which

can be seen in how the quantities flat-lined once their reached 85%. As a

result, prices reached well above normal levels. While labeling inflation as

supply or demand driven is straightforward, labelling it as supply or

demand caused is somewhat harder. That said if one category has to be

chosen then I would certainly opt for supply. Why? Because it is the supply

which is further away from pre-pandemic normal.

The main point, then, is that with more refined terminology

we can have both demand-driven and supply-caused inflation labels. We can say

that the recent rise in flight ticket prices is driven by rebound in demand,

but that the abnormally high flight ticket prices are caused by shortfall in

supply.

I think this story of airline ticket prices applies more

generally. What we have been observing since beginning of 2021 onwards has been

normalizing demand hitting below normal supply, which led to above normal

prices. Together with airline tickets it applies to many travel-related

categories, albeit with some of them I would argue it is more about

(temporarily) above-normal demand. It also applies to cars, where it is harder

to argue that demand is higher than before pandemic. And in some sense it also

applied to euro zone energy, where demand was abnormally low during pandemic,

and then in rebounded to meat depleted supply; of course, later on a decrease

in supply became dominant driver.

[1] Of

course, lower than pre-pandemic quantities does not on its own imply that

demand was lower than normal, because we also have to contend with the supply

side of the story. Simply, output can be lower even with demand above pre-pandemic,

if decrease in supply was large enough.