Czechia example

Consider the example of Czechia. Here are the facts:

- GDP has contracted for two quarters in a row, each time around 0.3% non-annualized. It is still below its pre-pandemic peak.

- Consumption has contracted for 5 quarters in a row, cumulatively 7.6%.

- Fixed investment has decreased in last quarter as well, albeit after strong recovery throughout the previous year and a half.

- The reason why GDP did not drop more is because net exports surged from their extremely low values reached during the pandemic period. In last quarter government consumption also helped a lot.

- Despite all the weakness, labor market is tight, with unemployment rate close to its pre-pandemic historical lows (in case you don’t know, it is ridiculously-sounding low at 2.1%).

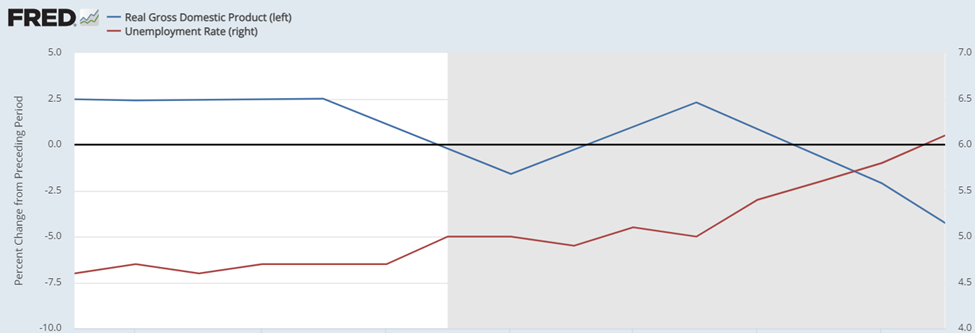

Is this a recession? In many dimensions it is. I mean, 7%

drop in consumption is simply gigantic; for comparison, during great recession,

there was almost no contraction. Now it is accompanied also by drop in

investment. And then there are the two successive declines in GDP, which would qualify

as recession according to the silly definition for “technical recession”. On

the other hand, the 0.6% drop in GDP is far-cry of normal recession. And above

all, it just does not feel like recession here on the ground. It just feels

like pretty depressing period for consumers.

Are there recessions in RBC models?

Yesterday, my boss had an interesting idea. Maybe we should look

at things like defaults and bankruptcies, rather just macro aggregates, when

determining whether something is or is not recession. I then built upon that idea

further and to put focus on self-reinforcing demand shocks as the key

aspect of recessions.

To see this start with following question: Are there recession

in RBC models? The question of recessions was one of the first controversies

between proponents and opponents of RBC models. The reason was that RBC models

explained fluctuations in output as fluctuations in the productive capacity of the

economy, rather than output falling below such productive capacity. This led to

the classical critique question of “What are the productivity shocks”, as

declines in productive capacity required negative productivity shocks. Such

shocks were at odds with the understanding of productivity at the time, given

that productivity was understood as akin to technology or knowledge. (By the

time I was reading this discussions I was not that puzzled: if you think about

productivity more broadly it feels very natural that it could easily decrease

following a shock; an example below).

Therefore, RBC models did and did not feature recessions.

They did in the sense of output declining in some periods of time. But they did

not, in the sense of output being below its (short-run) potential. I.e. there

were no output gaps. Only the move from RBCs to new Keynesian models allowed

for this possibility more broadly - albeit for a long time only to a limited

extend – by introducing nominal rigidities which could give rise to demand driving

the decline in output. And I think this contrast in perspectives is actually very

useful for current situation.

Real shocks and demand shocks

To see how the perspective of real shocks vs demand shocks

is useful now, consider back the case of Czechia. How can we explain the

current economic developments? I think it I fair to say that the economy is

undergoing large real shocks, both positive and negative. On the negative

side, the surge in energy costs is a very large and - crucially – real shock,

in that it changes the productive capacity of the economy. Moreover, at this

point in time it also leads to redistribution of output away from consumption,

which to some degree might be optimal. Meanwhile, the reason why output did not

collapse more is because at the same time the economy also faced large positive

real shock in form of global supply bottlenecks unwinding, which in turns I just

reversal of previous large negative real shock. (All of these are examples of

negative productivity shocks, since productivity and technology are separate).

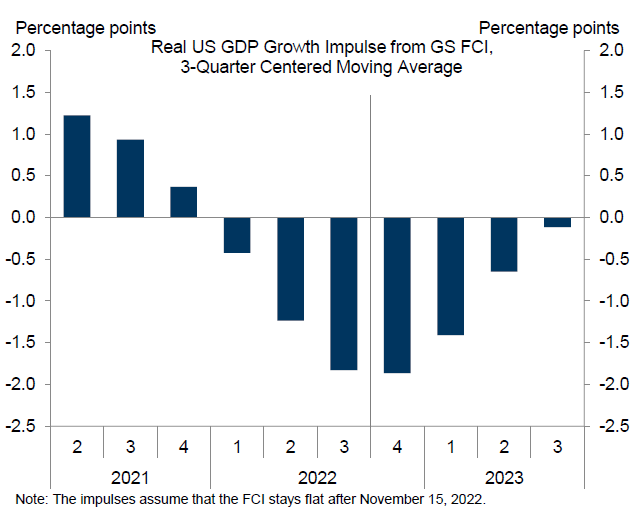

What is crucial, though, is the fact that these real

shocks have so far not been accompanied by negative demand shocks. In the

words, the typical mechanism though which recessions are self-reinforcing –

drop in demand causing further drop in demand through various channels – has not

kicked in. This can be seen in things like firms not firing people or

aggressively cutting down their orders and slashing inventories in response to uncertain

demand environment. It can be seen in that the financial channels being so far

very silent: there hasn’t been a wave of defaults leading banks to curtail the

supply of credit. Simply, while both consumers and firms are being hit by

shocks, they have not started worrying about the outlook in a way that would

cause them to change their behavior above and beyond what the shocks require.

No recession – but what is it then?

And this is why I don’t think Czechia is in recession. Neither

is any other European country so far. Simply, a recession really requires a

demand shocks to occur, and they have not occurred yet. I mean this in the

sense that demand is so far only responding to the real shocks hitting the

economy, and is not additional source of shocks, at least not to a significant

degree.

Of course, what is not yet the case might soon come to be:

there is nothing that says that firms will not lose their faith as their order

books are depleted and start slashing their demand and laying of people. And if

that starts happening, then it could gain speed pretty quickly. But in absence

of this happening, the economy will proceed along its current trajectory,

struggling to generate much growth before the effects of real shocks start to

reverse. Will the resulting path be a recession? I don’t think so. At the same

time I am sure it will not be fun either. Seems like we need a better terminology.

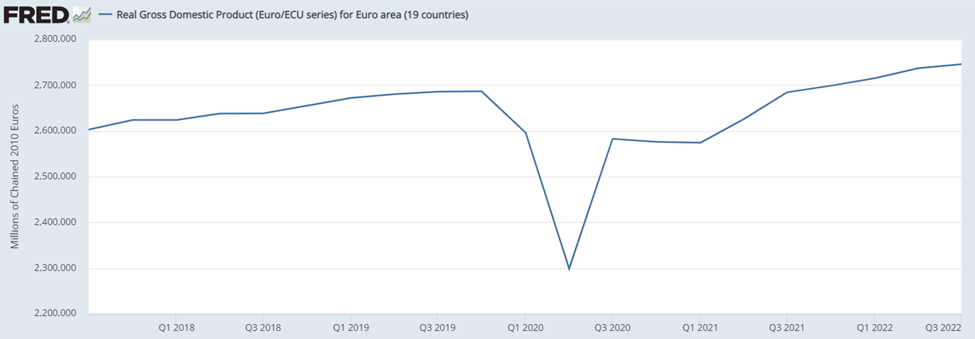

P.S.: Was pandemic recession

a recession in this view? I would say yes, because there was a demand

component. Financial channels were very alive and kicking. Firms like car

producers slashed they demand for inputs expecting slow demand from their

customers. Sure, the demand was not the dominant factor, which is why the

recovery from the recession was very different from great recession. Of course,

the main reason why demand played limited role is because of the demand

management: fiscal and monetary policy prevented collapse in demand and actually

gave additional boost to demand. But that is another story.